Coming of Age in the Time of Erdogan

Trying to make sense of the most turbulent years of my life in the wake of yet another disappointing presidential election

TW: Mention of SA, Suicide-Bombings, Violence, the EU

Sometimes I have to remind myself that not everyone was born on the precipice of a devastating earthquake that irrevocably altered the course of history1. Not everyone has had their first encounter with the concept of “sex” through third page newspaper articles describing the gruesome rape-murders of unnamed housewives by theirs husbands, reduced to their anonymity inducing initials. And not everyone has had to grapple with the fact that no matter how many years pass - and no matter how vehemently your elementary school social studies teacher emphasises the oh-so-important distinction between an undeveloped and developing nation - the country you were born into doesn’t go beyond being cited as the latter in government issued textbooks. Forever stuck in progression. Kind of like me, I think.

I was born in late June 1999 in Istanbul, formerly known as Constantinople and frequently mistaken for the capital of Turkey; and for good reason: a hubbub of Byzantine art and culture, bridging over the gap between Europe and Asia, Istanbul is as chaotic as it is historically one of a kind. Admittedly there was a time when I felt connected to that chaos, as if it were born into me. Sweating under my green army jacket as I ran to catch the last ferry to the other side home or berating my friends for not being able to navigate the seemingly non-existent bus stops, as I had learned to on my way to mall: I felt confident of my command of the city. But sometime between my 18th birthday and a lacklustre high school graduation that confidence faltered. As I started realising that the city that asked so much of my time, energy and gusto to simply exist on a day to day basis didn’t have my back as I seemed have its. And I started feeling resentful of the sheer amount of effort I put in it over the years.

Growing up in Istanbul, I never imagined that I would want to leave the big city. Some of my most distinct memories as a child where created in the backseat of my parent’s Toyota driving home from the mall on the weekends, reeling in the quiet exhaustion, gazing through the back window at the skyscrapers and creating drama filled lives for those who occupied them in my head to the backdrop of the sound of my mp3 (yes this was pre-iPodnano times). Seeing those orange tinted windows light up the dark made me feel like I couldn’t even begin to fathom living anywhere else. And in a way this is still true: I love being in big cities. I love how with every corner you turn you feel the possibility of something big and spontaneous lurking on the horizon. You can’t quite put your finger on what that something is but it feels tangible, as if it were weaved into the very fabric of the city. That uncertainty of outcome is what makes all the morning traffic induced headaches, rush hour crowds and exhaust driven nausea worthwhile. And for a while this was how I felt about Istanbul as well. Then came the bombings.

It started with the Paris attacks of November 2015: a series of coordinated terror attacks that targeted the city’s northern suburb of Saint Denis. A group of suicide bombers blew themselves up on the street among hoardes of people, another carried out a mass shooting at a death metal concert and the last opened fire on people wining and dining outdoors. A brutal sense of violation washed over me as I read the accounts of oblivious Parisians being gunned down in the cafes they had reclined to after a night out in the town. Here was a life I longed to escape to because I thought it existed outside of careless bloodshed that you had to laugh at to make do, with which I was so familiar. That illusion of a safe haven came crashing down as I mourned with the rest of the world. The cobblestone pavements of the city of my dreams were stained with dried blood, just as they would come to be in my hometown.

Violence has always been something I’m wary of. Ever since I can remember I’ve been afraid of walking alone at night for fear of being kidnapped or stabbed or worse: raped. It sounds paranoid but with the amount of horror story accounts you hear of young girls and women being sexually assaulted wherever humanly possible (on public transportation in broad daylight2 or even on a packed intercity bus at a rest stop3) it isn’t surprising that “rape” has been a recurring scenario in my nightmares since age 10. Despite this ever present fear of public violence that permeated my daily one hour commute to and from school I didn’t think much of it when my mom failed to wake me up 6:30 sharp one morning. Confused yet not all too upset about my extra 2 hours of rest, I went into the kitchen to inquire as to how and why I got to indulge in a healthy 8 hours of sleep on a weekday (!!) when she let me know that there had been a bomb threat at my school4. For all my fear of violence OUTSIDE, I wasn’t prepared for the possibility of it penetrating school premises and so I admit I was caught off guard. In my mind streets were public property: communal spaces where state authority loomed large, manifesting itself in sketchy alleyways and shady backroads, making them seemingly unregulated and dangerous, a breeding ground for casual violence and assault. But Deutsche Schule Istanbul, a self-important and therefore expensive private school built and regulated by the German government existed outside of the unjust laws of the land (which being a German high school built and regulated by the German embassy was partially true5). We, students and educators combined, were all too aware that life outside of the pearly gates of Deutsche Schule Istanbul was led by different principles than those which we chose to abide by within school grounds. We were wary of the limits of this collective delusion but we also knew the need of pretence to believe in a sense of purpose in order to survive (very much in the vein of that widely misinterpreted Joan Didion quote about how “We tell ourselves stories in order to live” ). And so when an anonymous bomb threat reached the German embassy on a random Thursday in the March of 2016, which further alerted regulatory staff to cancel school for the day, that well coveted sense of safety cracked. I stayed home too shocked to be delighted in the unexpected vacation from study. That Friday school commenced on paper but most of us didn’t go: our parents were advised to let us stay home. The day after someone exploded themselves on the Istiklal Street, a five minute walk from the aforementioned pearly gates, now tarred by rubble, smoke and quiet possibly human flesh6.

It was the beginning of the end in a way, because from then on a looming sense of mortality started following me around. Every time I took a step through a subway door I was sure it would be my last. My breathing would quicken during rush hour and my hands would get clammy from nervous sweating. Looking back, it is astounding to think of just how many times in the day I was genuinely sure I would die that year. I imagined newspaper reports of the hypothetical tragedy: a mass shooting on the subway wagon, no survivors; the barely recognisable face of a high school student of 18, dead among many. I thought about how my friends would eulogize my memory in tearful anecdotes; a smiling headshot of me on a coffin draped in green and cursive Arabic letters I wouldn’t have been able to read let alone understand… Imagining my funeral on my way to school all I could of think was how if i died right at this moment, i would die not even having had my first kiss… I don’t really know how to put into words the survivor’s guilt inherent to my being: I’ve never felt like I know why I’m among the spared, maybe that’s one of the reasons why I’m so fascinated by death. But then again I don’t think this is a unique experience. Especially when you’ve grown up surrounded by collective tragedy.

Existential ruminations aside that first suicide bombing was the first of many bouts of casual violence that my classmates and I would learn to get used to. Like I said, the fear of violence had always been there, but that year a series of happenings pushed repressed feelings of apprehension to the surface .I won’t bore you with the tedious details because I would like to believe that our lives amount to more than what our Western contemporaries would hastily deem “trauma porn”. And there is a certain self-awareness of “woe’s me” because we belong to that special caste of people privileged enough to (partially) buy their way out of the country. Nevertheless a succinct recap is necessary: the bombing of the Atatürk Airport in June was followed by the infamous failed Coup D’Etat Attempt in July (the memory of which has been monumentalised by various eye sores around the promptly renamed Bosphorus bridge). I was at home with my parents during both. The first left me shaking in tears as I resolved on my way to bed to leave for good after graduation. During the latter I hugged my mom in my parents’ bed as F16s that flew overhead rattled the windows of our apartment: for all my claims of pretence to bravery that year, I’d never been more scared in my life than on that sleepless night. But we made it through. Somehow I made it through.

And so I escaped to Europe: the continent where, despite not having been given the legal documents to prove it, I was technically born. I went to college. Graduated. Got a job. Found solace in the cheap beer and stagnant currency rates. Tried to fit in. Explained to people twice my age at dinner parties how the financial restrictions imposed on those from the far off non-EU lands prevented my parents from hopping on a plane and coming to see me whenever they wanted. They looked at me with their mouths agape and apologized for the privilege of not knowing about how Visas work. Smiling, I brushed it off. My lack of a EU passport wasn’t their fault after all. And yet more often than not I was reminded of the fundamental difference between me and them: the slew of political and social turmoil that had shaped so much my adolescent years.

All this to say what exactly? That I’m resentful of my peers abroad who haven’t been through half of what me and my contemporaries have been through before the age of 18? That I don’t feel guilty for not even considering the option of going back? That I still get irrationally angry at strangers for not having had to suffer through this past Sunday’s second round of presidential elections? That I can’t let go of the betrayal I felt by the indifference of those around me when the earthquake of last February flattened entire cities? I’m not sure exactly but I guess the point I’m trying to get across is an end in and of itself: articulating what happened and what keeps happening is the only way I can try to make sense of it. I feel crushed under the weight of the unbearable heaviness of feeling foreign - not just where I live but also to where I am from. The least I can say is that I know I’m not alone.

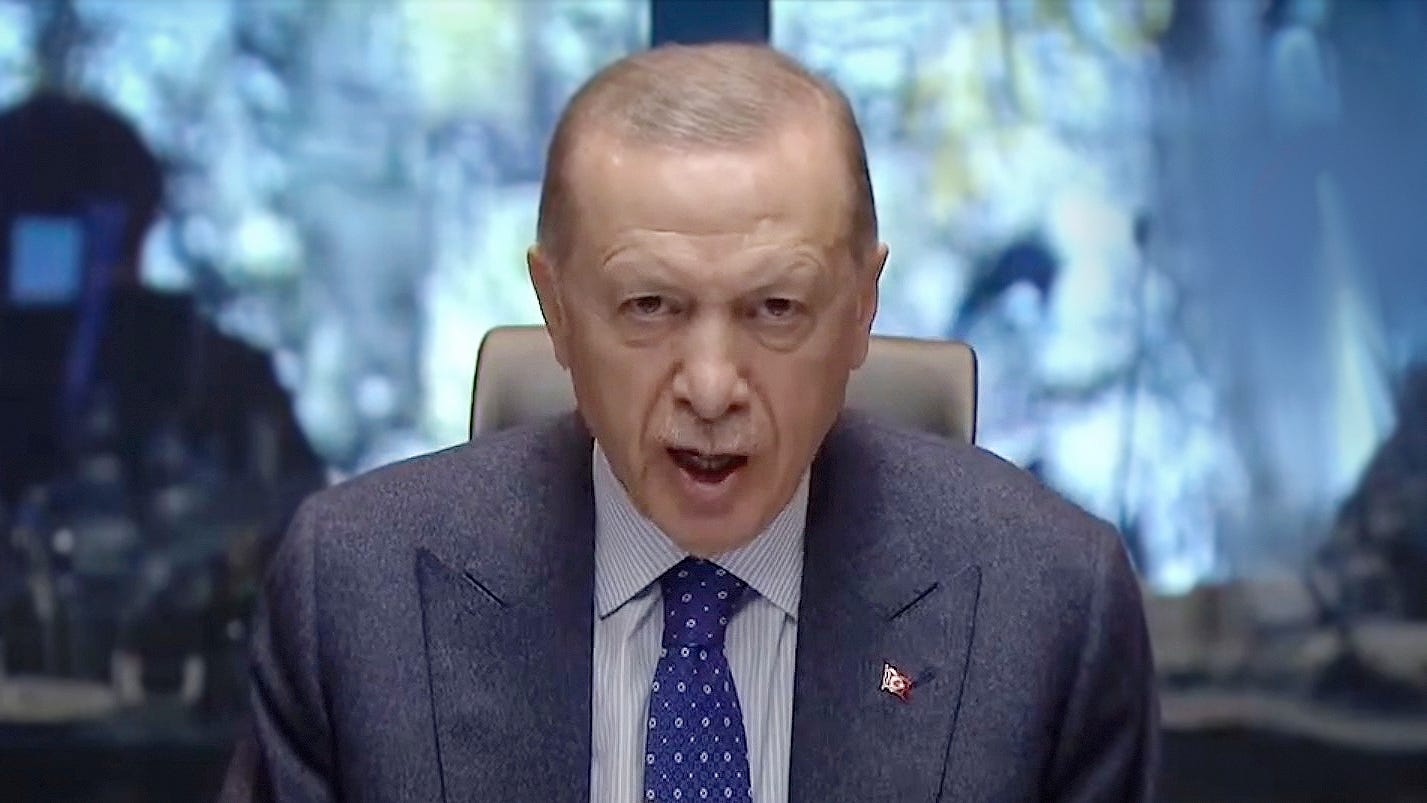

You will have noticed that in the recap of my teenage years I have refrained from mentioning He-Who-Shall-Not-Be-Named, save in the title. This is partially because I think He has been given too much credit in shaping every aspect of contemporary social and political life in Turkey, both in the practical and in the abstract sense: Everyday conversations about my homecountry, abroad or otherwise, revolve around Him and what He’s going to do next. It’s never about the specifics of any given situation. It seems the question of if and how He will respond haunts our every waking moment. And partially because I refuse to be defined by my suffering from a deified political figure .

It reminds me of when we were assigned 1984 by George Orwell as part of our high school curriculum. The parallels me and my classmates drew between Big Brother’s reign of surveillance and the present day were not exactly subtle: A formidable presence made all the more daunting by His deep, commanding voice addressing crowds of AK Party loyalists bordered on cartoonishly evil (if you think the Trump/Berzelius "Buzz" Windrip comparisons were on the nose just wait until you’ve read my 1984 book report). A comic book supervillain come to life. You would think that there would need to be certain degree of suspension of disbelief to make such a grandiose depiction of evil credible. Not if you’ve suffered the 10+ year-long reign of a “political” leader who regularly goes out of his way to remind you that you’re only half a person during the most formative years of your life7. We knew all too well how the banality of evil could become an all consuming force that defines national disposition. Even in this day and age.

And so here we are: post-second-round-of-the-2023-presidential-elections; trying to remain hopeful against all odds. All I can say is that I’m tired of fighting for my rights to exist as I am: Nothing more nothing less. There’s not much more left to say. In an ideal world I would’ve liked this to be an encouraging piece that motivates future generations to remain vigilant and hopeful. But every Godforsaken day that I spend on this Earth goes onto show that to each their own. I can only hope for the best as long as I am able to: And honestly I am at my limit.

There are many things here that hit a little too close to home . . . such as being born in a country that's stuck in a cycle of violence. Or that constant state of paranoia because you're fearing for your life. Or hell, even that tiny feeling of resentment because a lot of people outside don't have the faintest idea of how hard it is to leave a country . . .

Sorry you had to go through all this.

And as always, thanks for musing earnestly.