*Spoilers ahead for Oppenheimer and Barbie!!*

“Genius does not guarantee wisdom” a pointed remark supposedly made by the cynical chairman of the U.S. Atomic Energy Commission Lewis Strauss - portrayed by 90s-nepobaby-heartrob-turned-blockbuster-leading-man Robert Downey Jr. - in Christopher Nolan’s Opppenheimer, a biopic about a man colloquially known as the Father of the Atomic Bomb, rings true long after the end credits have stopped rolling. There is no denying that Nolan is one of the most influential filmmakers of our time - his dedicated possy of Nolanheads will make sure you acknowledge that - but with the exception of the profound yet ultimately unearned finale of Oppenheimer, I emerged out of the movie theater feeling rather distraught as to what all the fuss was about.

Oppenheimer is an amalgamation of two distinct genre films that have gained traction over the last couple of years: namely, the biopic of a misunderstood genius (Theory of Everything, The Imitation Game) and the revisionist courtroom drama tailored to the political sensibilities of modern audiences (The Trial of the Chicago 7). The first half of the film uses the cookie cutter formula of an effective but meandering biopic: tracing the perilous road that led Oppenheimer to the invention that would define his legacy for the foreseeable future. We first meet him as a graduate student at Cambridge, struggling with his laboratory technique and given to regular bouts of impulsive aggression - going so far as to attempt murder by injecting cyanide in a despised professor’s apple: this version of the original sin foreshadowing the chain reaction of destruction he will ultimately co-opt. After completing his Phd at the University of Göttingen Oppenheimer is recruited by US Army General Leslie Grove to form a group of physicists up for the task of the Manhattan Project, a research initiative of the US government to develop and build atomic bombs, in the census-designated laboratory of Los Alamos, New Mexico. A seemingly familiar all-star cast portrays each one of the now historical figures, who have had a hand in the making and the subsequent destruction of Oppenheimer’s professional career. From Nickelodeon star turned viral vlogger Josh Peck, who plays renowned physicist Kenneth Bainbridge, to one half of the Naked Brothers Band Alex Wolf, who portrays Nobel laureate Luis Walter Alvarez, the bizarre casting unwittingly test the limits of the audience’s suspicion of disbelief with every new addition to the ensemble. For a film so entrenched in the brutal real life consequences of militarized nuclear research, the plethora of vaguely recognizable faces which pop up on screen throughout its three hour runtime threatens to undermine the story’s credibility. After all, as Richard Brody of the New Yorker put it Nolan’s Oppenheimer is first and foremost a zero-sum morality tale, and not a nuanced character study of the man behind the bomb, in spite of its lead’s best efforts to make the most of the script's limited interpretation of his character.

In its second half, the film crosses into the aforementioned courtroom drama territory, wherein the successful detonation of the bomb over Hiroshima and Nagasaki leads Oppenheimer to question the morality of his intentions, thus far justified as having beaten the enemy to the punch. In a meeting with president Truman (Gary Oldman) he shares his growing consciousness of having blood on his hands. The president dismisses Oppenheimer’s concerns by handing over a handkerchief to wipe his hands clean. The scene is powerful, offering a much needed glimpse into the internal dilemmas of a man who is torn between what he believes to be his obligation as a man of science and its moral repercussions, which in the grand scheme of the film go unexplored. There is a lack of interiority to Oppenheimer’s character. He is depicted as an antihero, victim to a chain reaction of exterior forces beyond his control, but lacks a discernible personality that makes biopics of such a grand scale compelling.

Oppenheimer’s growing opposition to further nuclear research leads to a thorough government investigation and a subsequent security hearing, spearheaded by Lewis Strauss, who resents him for belittling his authority in the past. Instigated by the anti-communist sentiments of the McCarthy era a significant number of his former colleagues testify against him, certifying the counsel’s opinion of Oppenheimer as a national security threat and although by the end of the trial allegations of his old ties to the communist party remain unsubstantiated, he is revoked of his security clearance. Both Oppenheimer’s security hearing and Strauss’ Senate confirmation hearing are dense with dialogue and litigious jargon. The latter is shot in black and white, a deliberate stylistic choice - apparently intended to showcase the more objective side of the story - reminiscent of Nolan’s breakthrough feature Memento. The viewer is left to decipher the puzzle of the interwoven timelines and figure out the initiator of the witch hunt against Oppenheimer, ultimately revealed to be Strauss. Thankfully the predictability of Strauss’ betrayal is redeemed by the conclusive 10 minutes of the film, wherein Oppenheimer having been presented with a medal of honor by president Lyndon B. Johnson several years later, reflects on his actions that have significantly altered the course of human history. The overarching consequences of his invention and the fear of having started a domino effect of nuclear reactions he can’t undo freezes him in his tracks, staring into the abyss of a rain puddle, possibly pondering the foreseeable end of the world in the not so distant future. By the end he has realized the far reaching implications of becoming Death: The destroyer of worlds.

Though Oppenheimer’s ending makes up for some of its shortcomings, much like the man behind the bomb himself, it can’t undo the concatenation triggered by the problem at its heart: uninspired writing. In this regard the two female leads, Jean Tatlock (the mistress) and Katherine “Kitty” Oppenheimer (the wife) - played by Florence Pugh and Emily Blunt respectively - stand out. It is no secret that Nolan suffers from the same malady that is prevalent in the work of many a renowned male auteur: the inability to write well rounded female characters. But it is striking just how little he seems to regard these two women - who were in fact real people. They are relegated to figures of lust that entice Oppenheimer, momentarily distracting him from his professional pursuits. Pugh’s Jean Tatlock is the biggest offender here. We barely get a proper introduction to her “character” at the faculty party where she first meets Oppenheimer - as a red blooded communist who haughtily corrects his misquotation of Das Kapital - ‘till suddenly they’re in bed together. In true manic pixie dream girl fashion she picks up an original Sanskrit copy of the Bhagavad Gita mid-intercourse for him to recite in bed. They begin an on again off again relationship where she rebuffs his advances but expects him to return her calls without notice. Going off from his “characterization” of Jean you would think that Nolan, who has been married for more than a quarter of a century, has never had a successful romantic relationship with a woman in his life. Blunt’s Kitty is only marginally better. Written like a dubious pastiche of her less likable - and much more nuanced - counterpart Betty Draper, Oppenheimer’s resident wife is a struggling alcoholic with a sassy streak, the one and only personality quirk that keeps her from fading into the background as just another stock-adjacent character in his life (well that and the public’s evident desire to the see the big screen comeback of the Sassy Emily Blunt).

All that said Oppenheimer is ultimately the lovechild of its creator, Christopher Nolan, warts and all. It’s not nearly as tedious to sit through as his second to most recent endeavor Tenet but it also lacks the grand character-driven melodrama that made quasi-historical flicks like The Prestige or Dunkirk so entertaining to watch. There’s a lot more that can be said about the facts behind the story and I'm sure someone out there is more willing than I to tread those unfamiliar waters and point out the historical (in)accuracy of the film’s minutiae. But Oppenheimer, as a stand alone film, isn’t intriguing enough to warrant the discussion around it. And personally, I'm much more interested in dicussing the cultural implications of its main rival at the box office.

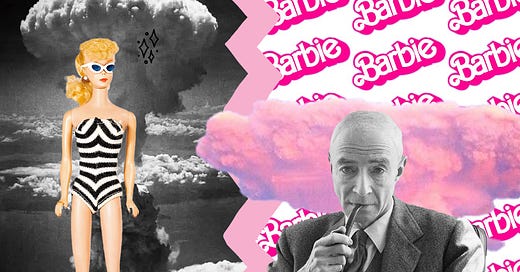

In an age where conglomerate capitalism has practically taken over every facet of the mass entertainment industry, the Barbenheimer hype of the past weekend has been somewhat of a breath of fresh air: a cultural demonstration of what could be the future of cinema. As hundreds of girls, gays, mothers, daughters, femme presenting individuals and unwilling boyfriends packed into the cinema wearing pink, I felt a sense of solidarity with my fellow moviegoers unlike I’d ever experienced before in my 24 years of existence. I was all too aware of the lengths Mattel went to push the cultural idiosyncrasy of Barbie™ as its resident “progressive” IP - with its slew of tie-in marketing campaigns that practically painted the internet pink - but my faith in the unabashed sincerity of Greta Gerwig’s cinematic gaze and childhood love of all things sparkly and pink, made me justify my purchase of a vintage pink gingham dress off of Etsy the moment I secured a ticket for the preview (And no the irony of critiquing Mattel’s insatiable consumerism right before purchasing an outfit specifically for the occasion of the Barbie™ movie is not lost on me).

After my initial watch, I have tried to keep up with the expected onslaught of online discourse on Barbie™ as much as I could. Hastily typed takedowns ranging from token conservative sentiments (“its anti-man) to run-of-the-mill liberal virtue signaling (“there isn’t enough representation) to pointing out the obvious ulterior motives of the corporate giant behind it (“it’s just an overglorified ad”) flooded my Twitter feed. In the ensuing days I have tried to read up on a variety of different critiques of the film, the most plausible of which I found to be the ones that exclusively focus on the hypocrisy of making a “woke” yet ultimately self-serving Barbie™ movie. Yet upon a recent rewatch I have decided that, despite all its shortcomings obscured by its overblown Meta-marketing, my critical verdict is ultimately that I really liked the Barbie movie.

Barbie opens up with a shot by shot parody of the first ten minutes of Stanley Kubrick’s science fiction epic 2001:A Space Odyssey. In Gerwig’s version the ominous black monolith is replaced by a giant rendition of the first Barbie doll on the market around which a group of wide-eyed little girls huddle, awestruck by the glossy sheen of its mount sized plastic legs. As the narrator (Helen Mirren) tells it, the dawn of Barbie encouraged a new generation of girls to leave behind their baby dolls and corresponding dreams of playing house for a whole new realm of possibilities, previously unimagined. The Barbie doll became a commercial tool of self-actualization, a malleable self, onto which little girls from all over the world could project themselves to be everything they could dream themselves to be, effectively solving all problems pertaining to gender inequality everywhere! Or so the Barbies in Barbieland think…

Within the universe of Gerwig’s Barbie, every Barbie doll resides in her own designated Dream House coated in matching shades of pink and located in the sugary sweet world of Barbieland, an Edenesque suburban paradise devoid of discomfort or shame that exists as a matriarchal ideal of our own comparably washed out and depressing Real World. Everyday is the same: Each Barbie wakes up in perfectly coiffed hair and makeup, dons a pre-assigned en vogue outfit and goes about her designated tasks, ending the day in an elaborate dance extravaganza and a subsequent girls-only slumber party. Though physically separate, Barbieland and the Real World more often than not reflect one another - and not always for the better - as our clueless yet loveable protagonist Stereotypical Barbie, perfectly brought to life by Margot Robbie, comes to find out one day when her perfectly arched feet are flattened to the ground: literally bringing Barbie down to Earth. Plagued by sudden thoughts of death and self-consciousness she seeks out the aptly named Weird Barbie (Kate Mckinnon) for answers, who looks worse for wear for having been played with too hard. Weird Barbie advises Stereotypical Barbie to journey into the Real World and find the little girl presumably responsible for her newly discovered ailments. At first hesitant to leave the routine comforts of Barbieland, the prospect of living with the horrors of *gasp* cellulite eventually convinces Stereotypical Barbie to hop into her pink convertible for the Real World, accompanied by her much-unwelcome himboyfriend Ken, played by s scene-stealing, bleach blonde Ryan Gosling.

Much to Barbie’s chagrin (and Ken’s delight) the Real World is the opposite of Barbieland in every way conceivable: casual misogyny runs riot, positions of power are dominated by men and even little girls go on tangents about how Barbie is a fascist for ruining women’s self-esteem for generations to come. Distraught by her discoveries Barbie seeks refuge at Mattel headquarters, a Jacques Tati inspired corporate maze of bureaucracy, where she runs into Gloria (America Ferrera), a Mattel employee whose inadvertent thoughts of death and celulite have brought Stereotypical Barbie into the Real World. Meanwhile her boytoy Ken has become enamored with the sense of superiority and power being a man in the Real World imbues in him by default, so much so that he hurries back home to teach all the other Kens the glorious ways of patriarchal living. When Barbie returns back home accompanied by her newfound friends Gloria and her Barbie-cynical angsty teen daughter Sasha (Ariana Greenblatt), she is shocked to find that the Kens have turned Barbieland into the hypermasculine - and subtextually homoerotic - playground of Kendom full of beers, bros and fur coats. In both of the screenings I went to, the self righteous, over the top antics of the Kens got the most laughs out of the audience: Gosling once again proving his impeccable comedic timing ( a fact that anyone who has seen the Papyrus SNL sketch prior to Gosling’s Kennaisscance was already privy to). From the Mojo-Dojo-Casa-House to the Depressed Barbie infomercial, these last forty minutes of the film are jam packed with endlessly quotable moments that seemingly hit the mark on every level, with the exception of one. Seeing Stereotypical Barbie lose herself on a self-conscious spiral Gloria gives what is essentially a pep talk on how impossible it is to be a real human woman, much less the plasticized representation of the Ideal woman. It’s evident that this moment harkens back to Jo March’s renowned “women, they have minds'' speech in Gerwig’s sophomore feature Little Women, but unlike its predecessor, which merged Louis May Alcott’s diary entries with the inner feelings of her semi-autobiographical protagonist, Gloria’s one-note monologue simply falls flat. It feels too didactic, too reductive to lecture the audience about the seemingly obvious gender-based double standards. Instead of a concise yet introspective articulation of the quintessential girl/woman experience, which I’ve come to expect from Gerwig, it reads like an infographic I would’ve stumbled upon in my formative years as a tween, foraging tumblr for dictionary definitions of “feminism”. Long gone are Gerwig’s Hannah Takes the Stairs days of denouncing things that are “explicitly about what they are”.

All the same, Gloria’s speech flicks a switch in Barbies’ heads as they become conscious of the cognitive dissonance required of women to exist under patriarchal systems of power without blindly acquiescing to its demands. What ensues is a series of “heists” devised by Stereotypical Barbie and friends to get each and every one of the brainwashed Barbies out of their delirium to teach the Kens a lesson. We get a perfectly choreographed musical dream ballet within a dream ballet sequence of the gloriously operatic ‘I’m Just Ken’ before the grand finale, where Stereotypical Barbie, having been through all that she has been through, takes her creator Ruth Handler’s (Rhea Pearlman) hands to leave the glossy facade of the dollhouse behind and become human. All loose narrative ends seemingly tied together and wrapped up in a neat little bow.

Much of the discourse surrounding Gerwig’s Barbie seems to revolve around the question of if it's feminist or subversive enough to warrant its massive global success. Gerwig herself has said that things can be both/and when talking about making Barbie: “I’m doing the thing and subverting the thing.” And to that I say yes/no. Barbie has always been a product of its time, upholding the status quo without foregoing the adaptability of its main tagline: “You can be anything” (Because “You can be anything as long as you adhere to societally embedded, sexist beauty standards under a patriarchal system that is structurally designed against you” isn’t as catchy enough). So it shouldn’t come as a surprise that Barbie the movie wasn’t as “anti-establishment” as Jean Luc Godard’s La Chinoise (Yes, this was an actual comparison someone on Twitter made pre-wide release). Or that Mattel, the multi-billion dollar company behind the venture, has already set in motion its five year plan for an auteur-IP-adaptation-cinematic-universe. The Barbie movie was never going to be the cinematic anti-capitalist radical feminist manifesto, bimbo-feminism made it out to be because then it would’ve had to go against the norm of the corporate backed blockbuster made with a clear profit incentive, which is in fact what it is. Barbie is the norm. She’s nostalgia-pilled capitalist realism that comes with matching accessories in a pink frilly box. She’ll tell you how beautiful you are for having aged into your fully human body and then sell you officially licensed Barbie pink anti-aging cream the moment you leave the theater. But this hypocrisy is chemically engineered into the plastic luster of the Barbie doll, which was created as a toy for little girls yet modeled after an adult gag-gift sex doll designed for men. And that original contradiction remains intact within the various critiques of the Barbie movie. Barbie is first and foremost a commercial product, one that encourages little girls to be whatever they want to be through consumerism. But she’s also a toy, albeit one that embodies and perpetuates the patriarchal female ideal, making it all the more convenient for little girls to project their aspirations and dreams onto without having to worry about the very real everyday constrictions imposed by the beauty myth. She is a “perfect” object by design which makes her an imperfect reference point for a movie about feminist social critique. But she’s also an accessible tool for self-discovery and storytelling. As Rebecca Liu writes in her review of Barbie for Another Gaze Journal:

“And so like its protagonist, who discovers that the world is unknowable and terrifying and finds herself to be flawed and impotent and disgusting, Barbie throws its failings at us and asks for redemption.”

The Barbie movie in all its self-referential, technicolor-Hollywood-nostalgia-bait glory is messy and convoluted and a bit all over the place. The emotional core, usually the hallmark of a great Gerwig project, is lacking. This is mainly because the film is much more concerned about addressing everything and anything Barbie has ever been - and possibly ever will be - in throwaway quips and gags rather than focusing on a well thought out story arc with emotional stakes. Barbie is all about the spectacle rather than the actual characters involved. It tries to be the fun popcorn movie for the “cultured” moviegoer - who reads The New Yorker and wears white tees with female directors’ names branded on them to the bar - and piggyback off of Gerwig’s cult following of sentimental twenty somethings to rebrand Mattel’s ubiquitous IP as self-critically feminist. And it somewhat succeeds in what it sets out to do: as a self identified sentimental twenty something with a soft spot for Gerwig’s filmography I sure as hell had a good time the two times I went to see it. And it’s okay to like a Barbie movie while being cynical about the intentions of the conglomerate giant behind it as long as we’re clear on what it is and what it is not. Or as Gerwig would say: you can critique the thing and still like the thing.

But then again none of this is new. We’ve been having this discussion about the Marvel cinematic universe for years now and despite the premature declaration of Barbie™ as the unofficial savior of the movie going experience, it seems like the only real change we’ll see in the future is the name of the mass-manufactured cinematic universe that’ll be disparagingly referred to as The Common Enemy when discussing the creative rut of mainstream cinema. The future of movies is looking very bleak indeed but at least Barbie™ has paved the way for it to come in pink.