The things my loved ones associate with me exude a certain degree of “me”ness or “menergy” in the same vein as Ryan Gosling’s channelling of Kenergy for his eponymous role in the new Barbie movie. One of them is cats: I am fundamentally and undeniably a cat-person, born and raised (my parents love to tell anecdotes of me constantly pulling the tail of our beloved Siamese when I was a baby). As such I have always been partial to defending the integrity of the feline species against the misguided accusations of the fiercely loyal dog-folk. Another is musical theatre: My early exposure to the Disney renaissance of the 90s made me fall in love with the dramaturgical device of characters breaking into song when life becomes a little too much to deal with on more realistic terms. And of course, the most character-defining and personable of my third-party-associations, which also happens to indirectly amalgamate the former two, is America’s-one-time-sweetheart-turned-global-superstar Taylor Swift™.

I discovered Taylor’s music at the impressionable age of 11 while browsing forums on Howrse, a free-to-play horse breeding simulation game I was introduced to by a friend. On paper - or should i say on browser- the game entailed taking care of and trading customizable virtual horses with other players but the main incentive for my regular log ins were the forums where you could discuss everything from tween pop culture news to friendship drama with like-minded equine enthusiasts: A sort of late-aughts MySpace for horsegirls. And so one day I came across a forum of girls ranking their top 10 favorite musicians. As could be expected of the core demographic of a horse-simulation-browser-game website most of the lists in question consisted of ex-Disney Channel acts making their due transition into more mainstream pop without comprimising their family-friendly and vaguely Christian sensibilities (Miley Cyrus, Selena Gomez etc.). However one name, which I failed to recognize, kept popping up at every other entry: Taylor Swift. And so like any other tween with unregulated internet access and too much time on their hands, I went on a Google-spree. I found the Youtube channel for Taylor Swift™ and clicked on every music video she had at the time ‘till one of them sold me on what is now the quintessential Swift narrative: lovestruck girl tries to make sense of her feelings with sparse but effectively direct storytelling and a catchy hook. And if you’re wondering which song was responsible for kickstarting my decade long parasocial attachment to a morally dubious Pennsylvanian woman 10 years my senior, I wouldn’t hesitate with my answer: “It was “Our Song””.

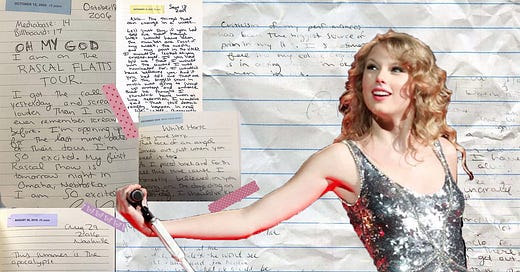

And the rest, as they say, is personal history: Much to the chagrin of my parents I have been a certified Swiftie™ ever since that faithful day in the summer of 2009. When I look back on my 10+ year long devotion to now-a-multimillionaire-superstar who has been scrutinized endlessly in the media for her personal relationships, career ambitions and moral obligations as a woman in the public eye from ages 16 to 33, I notice a dramatic shift in the cultural discourse around the Taylor Swift™ persona. I am old enough to remember the textblock meme that made the rounds in the early days of the internet, poking fun at Swift’s timeline of failed romantic relationships (ironically years after the tired old joke had run its course she released a song called Anti-Hero). I recall staying up late to watch the 56th Grammys just to hear the roundtable of music critics providing live commentary dismiss Red’s “Album of the Year” nomination as trite because of its mainstream appeal and sentimental subject matter. And I remember how Pitchfork, the much respected- and every bit as pretentious - online music publication, refused to review any of Swift’s albums until indie musician Ryan Adams released a cover album of 1989 in 2015 (their oldest review of Swift’s work dates back to 2017 whereas Adams’ cover album was reviewed within the week of its release).

There was a time when Taylor Swift™ was lauded as a role model for girls and young women everywhere. With her demure demeanor, prudent yet witty responses to inquitive questions about her personal life, her modest way of dress and lack of major scandal, Swift projected an alternative to “The-Good-Girl-Gone-Bad” archetype, so prominent in early aughts pop music. The sociocultural origins of “The Bad Girl” could be traced back to the central dilemma of the Madonna-Whore complex, which perceives women along the lines of the dichotomous “Virginal Mother to Sinful Whore” spectrum. As such “The Bad Girl” functions as a transitional role commonly employed by child-act turned popstars trying to break into the mainstream by shedding the guise of innocence and sexual immaturity associated with girlhood. For most of her career, Swift’s image has been posited against “The Bad Girl”, as representative of the other end of the spectrum: the self-appointed good-girl-next-door.

In his seminal work “The Presentation of Self in Everday Life” American sociologist Erving Goffman breaks down social interactions into performances between teams of performers and audiences, wherein the performers co-operate with eachother in order to foster an effective impression, consistent with the expectations of the audience. In this sense the presented self of the individual is understood in terms of a performed character or “(…) as some kind of image, usually creditable, which the individual on stage and in character effectively attemps to induce others to hold in regard of him” (Goffman 1959:252). In other words, the individual presents their sense of self in a performance designed to evoke attributes of a certain character.

Applying this theoretical framework to the public persona of Taylor Swift™, which has been well documented to have been carefully curated to appeal to the widest market possible, we find that Swift, as the designated performer, has mastered the art of impression management. Goffman defines impression management as the collection of attributes and practices employed by the peforming party in order to successfully stage the desired character. As such he specifies the measures used by “the performer” in order to sustain the impression of a consistent persona: namely dramaturgical loyalty, dramaturgical discipline and dramaturgical circumspection. In the case of Swift, it is clear that she depends on the loyalty of those in her team as well as her ever-growing slew of devoted Swifties, who are an essential part of her performance of Taylor Swift™, in order to maintain the impression that she is the well-intentioned good girl personified. To that end, Swift’s discretion when it comes to the subject of contemporary politics could be taken as a show of dramaturgical discipline, wherein she demonstrates a certain degree of self-control in order to keep her presented self politically ambigious. Although Taylor Swift™ has come a long way from tactfully dodging questions about who she’ll be voting for in the coming midterms (she went so far as to endorse Joe Biden’s campaign with self-baked cookies during the 2020 presidential election), Swift nonetheless avoids making statements about more divise political matters until a working consensus has been reached and her support of which would be consistent with her image as a public figure (such as when she retweeted Michele Obama’s response to the Supreme Court’s overturn of Roe v. Wade in 2020). These fairly recent shows of mild political conscioussness double as an example of dramaturgical circumspection, in that they showcase the adaptation of the Taylor Swift™ persona to the changing circumstances of the times. As Goffman states “The performer who is to be dramaturgically prudent will have to adapt his performance to the information conditions under which it must be staged” (ebd. 222). Thus in the age of Buzzfeed listicals spreading the “Lean In” gospel of - the more inclusive equally as palatable - choice feminism and the democratization of access to information as well as political power through social media, Taylor Swift™ has had to become an active advocate for equality in order to keep her image intact. Swift herself puts this strategic change of heart quite succintly in her Netflix documentary “Miss Americana”: “I need to be on the right side of history”.

Additionally Goffman highlights the protective practices employed by the audience to protect the farce of performance as well as the obligation of the performer to show tact in situations in which the fostered impression is at risk of being revealed as inauthentic. The protective practices in question are easy to recognize in the cult-like devotion of Swifties to the Taylor Swift™ persona. So much so that when she seemingly decides to date someone who is “inconsistent” with the performed character they take to Twitter to petition against it. These efforts of the audience are intended to help Swift keep up appearences by hinting at the inconsistency of her performance, which jeopardizes her fostered impression of the - now politically sensible - “Good Girl”. It is no surprise then that shortly after the public backlash news broke out that Swift’s alleged whirlwind romance had abruptly ended.

Swift’s show of tact throughout her career to maintain the integrity of her performed self reveals something essential about the presentation of girl-/womanhood in everyday life. Although most of us don’t perform ourselves on such a massive scale, the gendered rules of conduct Swift abides by to foster the “right” kind of impression are all too familiar. The public perception of her image has shapeshifted from innocent-girl-next-door to clingy-serial-dater to pink-capitalist-girlboss-icon to eco-terrorist-celebrity to white-feminist-ally. Her performed self has always remained malleable enough to appease the requirements of the cultural Zeitgeist, which is probably the reason why she keeps on breaking streaming records and selling out world tours nearly three decades into her career. Whether you have an irrevocable attachement to her diaristic songs, which by their very confessional nature are an essential part of her performed self, like I do or hate her for the authentic artificiality she has come to master, you can’t deny that Taylor Swift™ knows how to put on a show.